Solo shows at SLAG Gallery, from February 2, to March 11 2023

Stella Waitzkin

By Eleanor Heartney

Books are repositories of human knowledge and portals to imagined worlds. But they are also (although this concept is increasingly endangered in our digital age) tactile objects composed of paper covered in ink and bound together in handheld volumes. In this latter guise, books can be subject to any manner of indignities and transformations, a reality that has inspired countless artists. Books can be singed and covered with lead (Anselm Kiefer), cast in concrete (Rachel Whiteread), even dissolved and fermented (John Latham). But rather than diminish their power, such treatments only affirm how central books are to the human imagination. The multiple seductions of books are central to the mature work of Stella Waitzkin.

Born in 1920 in New York City, Waitzkin came of age as an artist during the tumultuous 1950s and 60s. She gained critical recognition and commercial exposure in the 1970s and 80s, appearing in twelve solo and numerous group shows and continuing to make art until she died in 2003. In the years since her death interest in her art has grown. Her work is held in many collections, among them the Smithsonian, the National Gallery of Art, the Walker Art Center, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Museum of Modern Art, the Jewish Museum, and the New York Public Library. Several large assemblages based on arrangements of her works from her apartment are owned by the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin.

Like so many women of her generation, Waitzkin followed a circuitous career path. While young, she explored theater, hosted a radio show on beauty tips and attempted to settle down in a conventional marriage. Eventually, the pressure to conform was too powerful and she sought liberation from the prescribed roles of wife and mother through art. In the early 1950s Waitzkin studied with Hans Hofmann and Willem de Kooning and became a painter. By the end of the decade, she had left her husband to pursue the artist’s life in Greenwich Village. There she threw herself into the feminist and anti-war movements and began expressing her dissatisfaction with contemporary society through a series of feminist performances. In 1969 she moved into the Chelsea Hotel, where she would retain a residence until her death. This legendary haunt of artists, writers and musicians became the incubator of the works for which she is best known: assemblage sculptures that combine found and fabricated articles in a manner that breaks down the barrier between art and life. For the New York avant-garde of that time, traditional definitions of art had become meaningless. Rauschenberg put a tire around a goat and made his bed into a painting. Louise Nevelson salvaged materials from construction sites and pieced them together in moody black architectural structures. Like them, Waitzkin was exploring the new possibilities emerging from the wreckage of the old rules.

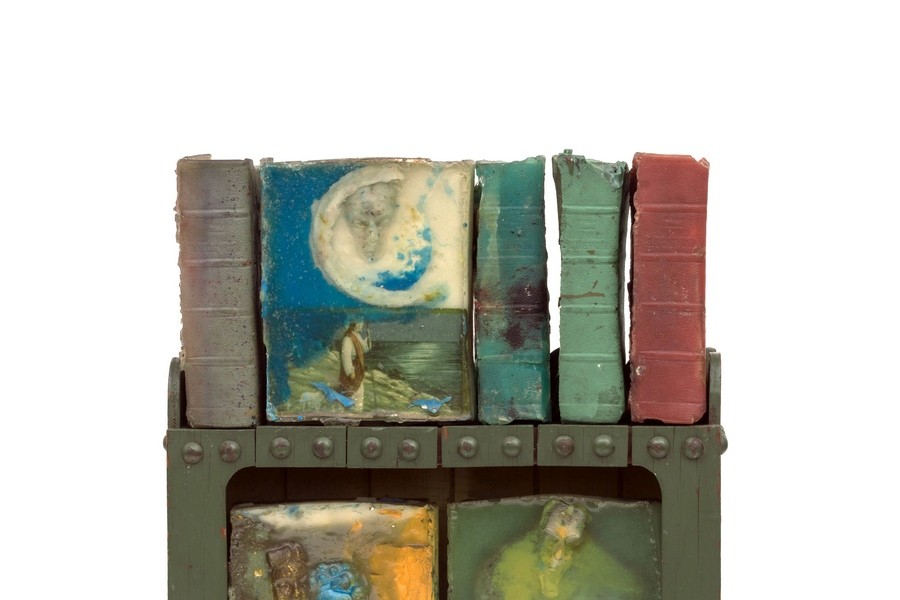

Waitzkin found her métier in books. After experimenting with glass and metal, she settled on cast polyester resin as her preferred material. Its semi-transparence captures light while suspending any object encased within it in a milky translucence. She learned how to color the resin, giving the works a mysterious glow. Books cast in resin are defamiliarized. Traces of the embossed patterns on their covers, bits of bound leather and even at times a title remain visible. But the objects themselves are now something new. Waitzkin incorporated other artifacts into some of the sculptures –doll heads, casts of her own or friend’s faces, birds, fruit and fish and other trinkets. She also used resin to cast other objects. One example is a series of casts made from a relief, possibly cast from the cover of an antique wedding album, representing a pair of lovers. In what was perhaps a slightly cynical comment on her own marital experiences, she titled these works Pre-Nuptial Agreement/Marriage Vows. Waitzkin displayed her resin books in various ways. Sometimes they existed as singular objects, and sometimes she grouped them spines out, piled up or face out. They might be propped up with bookends or cast as open volumes from which objects protruded, literally evoking the idea of narratives spilling from a book. In her Chelsea apartment, Waitzkin’s art works surrounded her. Arranged on shelves, they became elements in ever-changing wall size assemblages.

Waitzkin’s cast resin books have the frozen stillness of relics and the poetic resonance of shards unearthed in an archeological dig. Writings about Waitzkin’s work frequently stress a comment she made in an artist statement: “Words are lies.” This is often used to suggest that she regarded books as suspicious objects that needed to be silenced. But it is important to know that the statement continues, “I make the books to get away from the word. When I make the books, I feel like I’m telling folk stories; it’s all there inside the book. You don’t have to necessarily read it, see, because you already know the whole thing by heart.”

This suggests that Waitzkin saw herself as a storyteller. What kinds of stories do these works tell? There is pathos and redemption in the resuscitation of discarded items. The objects she chose to incorporate suggest an old-fashioned version of femininity. The birds, flora and cast heads have a Victorian quality, imbuing them with an aura of nostalgia. And yet, trapped as they are in resin and almost melting before our eyes, they also hint at Waitzkin’s unwillingness to succumb to traditional expectations. The books themselves, resembling fragments of a personal library, speak of home and domesticity – a place both of sanctuary and imprisonment. And while the assemblages often exhibit a wry wit, they also convey a sense of melancholy made more powerful today by the awareness that physical books themselves are rapidly becoming relics of a vanishing world.

A sign displayed in Waitzkin’s library/studio read: “These Books are Paintings.” With this, she indicated that her resin books are not meant to be read in any conventional sense. They speak the language of color, form, material and light. But for all their formal beauty, they are like ordinary books in one striking way. They contain worlds, ushering us into a magical realm of memory, dream and emotion.

Ariane Lopez-Huici

By Barry Schwabsky

Is Ariane Lopez-Huici a photographer, or a painter? Yes, and yes. And a special kind of director, too—one who turns the space of the studio into a theater in which the model is free to act, to move, to express, seemingly, anything. No rules. She moves with them, following their lead. “It’s almost like a dance,” she says. The photographer is in motion, but discreetly so: Our attention remains focused on the model. And however wildly expressive the model’s movements might be, the resulting images have an almost classical clarity. However ecstatically naked the model, however lovingly appreciative of the inherent sensuality of the model’s flesh the photographer may be, the image makes ecstasy durable, almost sculptural, and the photographer’s gaze is non-possessive. It desires only that the other person, the model, should be, and to bear witness to the manifestation of that being.

Much has been written about the distinction between nudity and nakedness. Lopez-Huici’s models are never nude. A nude is a model who has shed his or her clothing; nudity accepts being clothed as the normal human state of appearance. By contrast, in Lopez-Huici’s images of, say, Aviva or Dany, I glimpse something different, a being that is whole, that is pure expression, that has not, you might say, had to be stripped. And when I see Maria Mitchell swirling a great piece of fabric around herself—I don’t even know if it is garment or just a length of white cloth—I feel, on the contrary, that she has elected, not to clothe herself, but to shed, for a time, in complete freedom, her nakedness. The fabric appears, not as a covering, but as another kind of dance partner.

But the pure photographic image is not the end of the story. The photographer becomes a painter. Aggressive yet joyous marks of acrylic paint: Looking at them, I sense that yet another dance has taken place. The photograph finds its partner in paint. There’s joy in seeing how Lopez-Huici, an artist already completely fulfilled in the medium of photography, finds herself free to release another kind of artist in herself, not (of course) because I imagine it is better to be a painter than a photographer, but because it is better to be plural than to be one thing. These images are each in themselves plural; and because the artist has allowed herself to be plural, both photographer and painter, she offers us more to see, more to dance with in the mind, than photography or painting alone. And, of course she has already entered plurality, as well, in her collaboration with her model, which makes both of them something other than what they would have been alone. And then there is a third stage, in which the painted photographs become, again, photographs—Loepz-Huici has spoken to me of the pleasure she takes in the photographic enlargement of the painterly gesture, what she calls a “magical transformation.” But these photographs have painting inside them as the photographer has the art of painting inside her—art and artist alike in the plural.